This is Part III of our ongoing “The Lookout” series exploring the stories and history behind Outer Shores Lodge, and the site on which the lodge sits. If you missed our first two entries into the Logbook in this series, ‘R. Bruce Scott & Outer Shores Lodge – Part I,’ which tells the story of Bruce Scott’s arrival in Bamfield, his days at the cable station, and the first cabin built on the site where Outer Shores Lodge sits today, and ‘R. Bruce Scott & Outer Shores Lodge – Part II’, which looks back at Scott’s belief in the potential this part of the world had to positively affect the way people think and feel about their connection to the natural world, be sure to read them here.

“Oh, they thought I was crazy. Most people did. Even my friends thought I was crazy to invest in Bamfield and buy property, but that’s alright. But I was still thrilled and enthusiastic. I still believed that one day it would become one of the principal seaside resorts in western Canada.”

– Bruce Scott

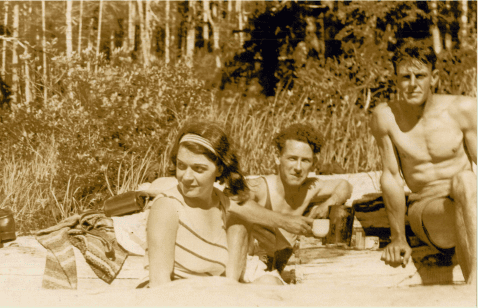

As we wrote about earlier in this series, Bruce Scott had now turned his little cabin on the point into what was then known as Aguilar House (now Outer Shores Lodge), one of Bamfield’s first tourism-focused endeavours, welcoming guests to participate in Scott’s enthusiasm and desire to share Bamfield and beyond with others.

Bamfield and Beyond

At this point, he was already nearly two decades into his campaign to have a national park created in order to protect the region he cherished so much. In the 1950s, it looked as though perhaps his continuous push was finally gaining traction when the government sent a couple men out to get a better sense for what Scott was promoting. Scott said his approach was “to go for a small park area [rather] than a large one at that time.”

He guided the government representatives around the region and they were convinced by what they experienced. While it still wasn’t granted park status or protections, the visit did get a land reservation placed on the area, which was a crucial step in Scott’s vision finally being realized. But there was still a long way to go.

The Long Journey to Pacific Rim National Park Reserve

The land reservation was a shot in the arm for Scott’s efforts and he worked diligently to ensure he didn’t lose the little bit of momentum he had finally been able to drum up. He would spend much of the 1950s and 1960s writing to government officials and politicians, passionately describing his belief in the potential for the region and reconfirming his offer of land for the initiative.

As The Bamfield Historical Society notes in their well-researched work ‘The Life and Legacy of R. Bruce Scott,’ “between April 26, 1963 and February 18, 1966, Scott entered into correspondence with the Department of Recreation and Conservation, Parks Branch, the Canadian Overseas Telecommunication Corporation, and Thomas S. Barnett, MP, in an attempt to secure lands at the old cable station for community use. In the end it was to no avail.”

Still, he continued to advocate for his vision with seemingly anyone and everyone who might have him to present his promotional slides and describe his vision for Bamfield and the Port Renfrew area. And that’s when Scott’s persistence and insistence finally found the right audience at the right time.

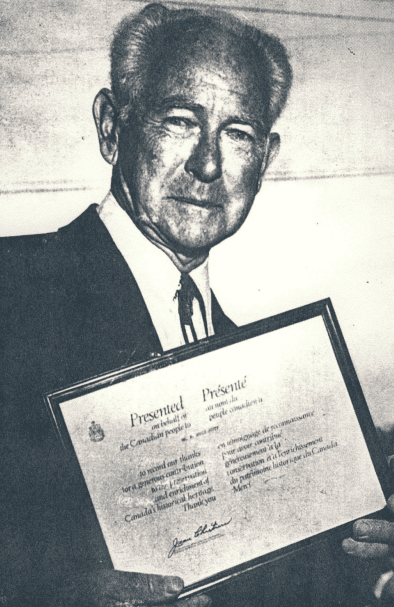

presented to him on behalf of the Canadian people in honour of his contributions to the establishment of a west coast park.

Credit: The Bamfield Historical Society

It was during a Victoria Fish and Game Club luncheon in honour of future Canadian Prime Minister Jean Chrétien, who was the Federal Parks Minister at that time, that Scott’s mission finally found its path forward. Minister Chrétien was very intrigued by what he saw in Scott’s oft-shown presentation, and here was someone who had the jurisdiction to do something about it.

As reporter Margaret Williams wrote in an article for The Islander entitled ‘Bruce Scott; The man and his dream,’ “[Chrétien] then got a helicopter, flew to Carmanah Point lighthouse and then walked part of the trail. When he returned to Ottawa he enthusiastically reported to the next cabinet meeting so that when [then Prime Minister Pierre] Trudeau came to the coast he did the same thing and agreed that the region should be preserved.”

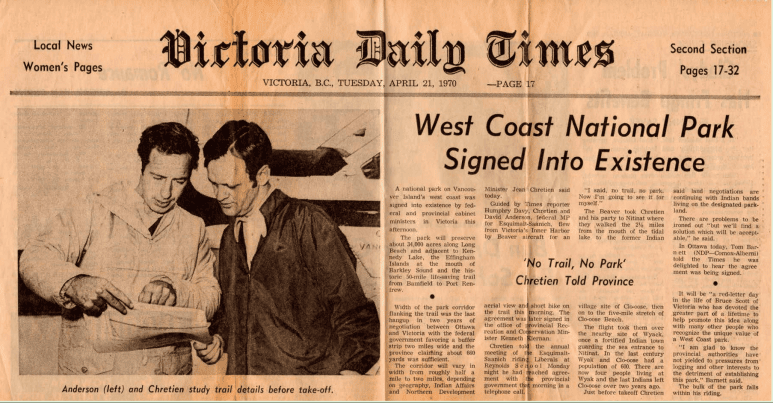

On April 21, 1970, the park was signed into existence by federal and provincial cabinet ministers in Victoria. The opening ceremony was attended by Princess Anne of England, where Jean Chrétien presented her with a driftwood abstract sculpture by local artist Godfrey Stephens.

‘It will be a red-letter day in the life of Bruce Scott of Victoria who has devoted the greater part of a lifetime to help promote this idea along with many other people who recognize the unique value of a West Coast park.’

– The Victoria Times, April 21, 1971.

“Keep Looking For Something Which Is Interesting”

With his long mission finally accomplished, Scott’s latter years saw him return to Victoria permanently, but it seemed achieving his goal, while rewarding personally and extremely important for the conservation and celebration of the region, left him feeling somewhat adrift.

“But a little bird or a little voice told me that, ‘Keep looking for something which is interesting,’” he said in a 1973 interview. And while he’d written numerous articles for newspapers in order to advocate for his passion project of the creation of the park, it also served to set him up for his next passion; writing.

As The Bamfield Historical Society identified, Scott’s many articles inspired him to expand his material, which led to him writing five books.

The first, ‘Breakers Ahead,’ was a history of shipwrecks on the Pacific Coast. He followed this up with a book more in line with his articles written up to that point, one designed to continue encouraging interest and appreciation for his beloved region; ‘Barkley Sound: A History of the Pacific Rim National Park Area.’ Next came his third book in his trilogy of books about the history of West Vancouver Island with ‘People of the Southwest Coast of Vancouver Island’, which includes a number of chapters on the history of Bamfield. His love of Bamfield and his time in our coastal wilderness community was explored extensively in his fourth book; ‘Bamfield Years: Recollections.”

His final work, ‘Gentlemen On Imperial Service: A Story of the Trans-Pacific Telecommunications Cable,’ saw him turn his attention back to those earliest days of falling in love with Bamfield and the future Pacific Rim National Park Reserve. It was a love at first sight that would serve as a guiding light from those first moments in his younger days as a committed cable wire operator simply making his way along the trails and finding a lifetime of inspiration on them.

Robert Bruce Scott passed away on October 10, 1996 at his home in Victoria, B.C. Outer Shores Lodge is committed to carrying his vision, his mission, and his approach to stewardship of this site forward in everything we do. We are proud to be able to take up the mantle Bruce Scott helped to establish here, and look forward to sharing more stories of Bruce Scott and the many other stewards of this site and the larger region both here in our The Lookout” posts and, of course, when you visit us at Outer Shores Lodge.